John K Lynch grew up in Mullagh and has a vivid recollection of working on the bog over 50 years ago. He shares them with us here*

“The story of Killyconny Bog, Cloughbally Bog, Killycunny Bog, Leitrim Bog, The Big Bog, or whatever name you may know it by, is set to become a wonderful public amenity over the next few years… so let’s help it succeed along the way.

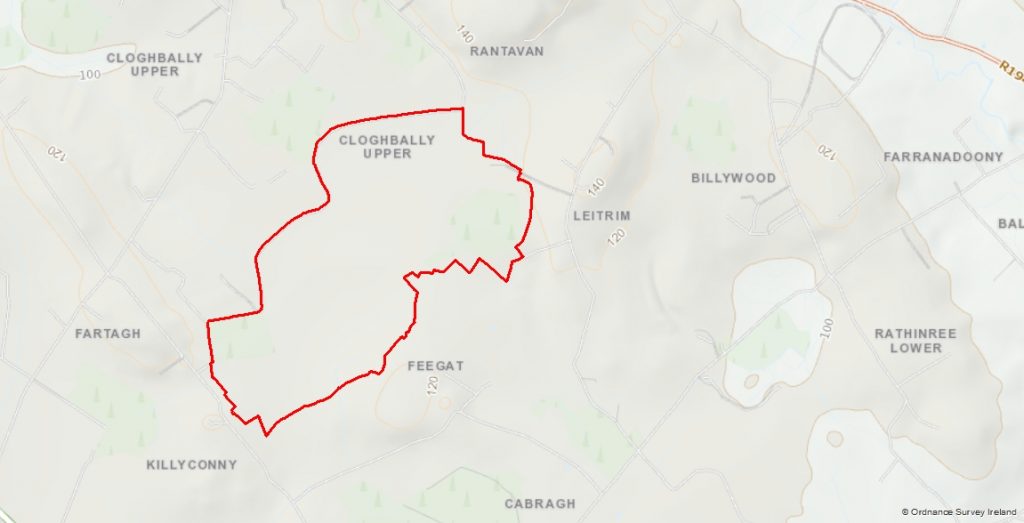

The present bog area in question covers approximately 190 hectares (472 acres). However, it is interesting to mention the Down Survey carried out in Ireland by William Petty from 1656 to 1658. This was the first ever national survey of land in the world, whereby the resident Catholic Irish landowners had their land confiscated and redistributed to Commonwealth soldiers and other Adventurers . The Survey maps of the period show a continuous stretch of bog – 1,709acres, 1 rood and 24 perches (691 ha) extending South East from Murmod to the Leitrim/Fegat and Killyconny townlands on the Co. Meath border, and name it “The Great Bogg” and “The Red Bog” respectively.

At that time the area would have been for the most part inaccessible, flooded with a non existent road structure and basically unrecognisable to us today. Prior to the Cromwellian Survey, the area would have been natively referred to in the spoken language of the time, Gaelic. The adjacent townland of Feegat in the South East area of the bog has its roots in the Gaelic form of the name “Fiodh na gCat” translated “The Wood of the Cats” – these animals would were wildcats, similar in appearance, but much larger and vicious than the present domesticated cat and were very common in the countryside. Dr. Philip O’Connell a noted historian of the early 1900s and native to the area stated that the Great Bog was also known as “Monuorogata Bog” – “Moinfhear na gCat” – that is the marshy meadow or bogland of the cats. The 190 ha of Killyconny Bog as it is now officially referred to, is for the most part as it was topographically over 350 years ago.

Memories of the bog are fast disappearing and it is not untrue to say that most people connect the word to a wet morass of swamp and marsh – a wild foreboding place to be, especially in bad weather – where one could easily vanish, never to be found again after being swallowed up in its black mass! Bogs of course are much more interesting places than that. They are in effect, a reservoir and library of the earth’s flora over thousands of years and of course are recognised as the earth’s important carbon sink. After the retreat of the ice sheet covering Ireland some 15,000 years ago, the stage was set for the formation of our bogs. Irish bogs are between 5,000 and 10,000 years old.

They are unique in the world and a very important feature of Irish landscape. Rich in biodiversity, they require to be waterlogged to achieve growth and this poses problems to adjacent agricultural land that can be overcome. Our ancestors committed gruesome acts on fellow human beings, buried their remains in bogs and the natural preservatives contained in turf bogs – tannin – leave perfectly preserved bodies when found hundreds of years later – albeit the skin being tanned like leather. Subsequent examination by forensic archaeologists leads us to a better understanding of the deceased’s diet, lifestyle, age, etc. We describe the product of the bog as turf, the same word as used in the German language while the English use the word peat. Bogs insofar as our neighbours on the adjacent island were concerned, were in their mind-set only associated with the native Irish and therefore used in a pejorative sense, to describe the Irish as “boggies”. I suppose it was as a result of the preponderance of bogs covering our landscape, which over the centuries were the only source of fuel to heat our primitive dwellings and modern homes, even up to the present time. Carbon dioxide emissions and the phasing out of fossil fuels are some of the reasons that have now ensured that our remaining bogs are places of preserved natural heritage and sites of minor industrial archaeology with accompanied associated folklore traditions.

My earliest recollections of “being on the bog” was at 5 years of age in 1955.

We had a “bank” or plot of turf on what we called Leitrim Bog and it came with the farm of land. Turf banks were measured in perches (and these are not the fish!) – 1 perch equaled 5.5 yards which is equivalent to approx. 5 metres. My father (Harry) and my grandfather (John) cut some turf that summer.

John and Mat Reilly, Leitrim had an adjacent “bank” and as far as I can remember, they also cut turf that season. John Bracken, John Gibney, Nicholas Dolan, Ballintlieve, George Bough, Rantavan, Patsy Cassidy, Shancarnan, Jimmy Smith, Leitrim were regulars working on the Rantavan side of the same bog. I also seem to also remember Peter Lynch, Leitrim on the bog and cutting somewhere near us. John Travers whom we often spoke with and two or three other turf cutters worked on the Killacunny side, but I don’t remember their names.

Leitrim Bog was relatively quiet compared to the Rantavan and Cloughbally side where all the action was and which was a hive of activity. I distinctly remember that the boundary of our turf bank was marked by a crab apple tree which my grandfather had planted years earlier and which was growing there until relatively recent times. It was a great marker and aid to location as all turf banks looked the same. In addition, there was mature beech trees planted on both the Lynch and Reilly banks. The two families it would seem must have planted them in the very distant past – over 100 years ago – although this may not be entirely true for other reasons. This bank of turf was quite near to Rantavan townland, but to access it required travelling the long distance by public road up to Leitrim taking the lane off to the right leading down to the bog, crossing a “kesh” over a main drain and into the afterbanks of the bog – a distance of over 1 mile. Years later in the early 1960s, I helped my father cut some of the beech trees with a crosscut saw. The Reillys’ also cut some of their tress the same year. This was hard work, but the big crosscut saw seemed to fly through the huge timbers.

We relocated to cutting turf on the Rantavan side from 1956 onwards. This turf bank was adjacent to our farm and very convenient. As we did not own the bank, my father rented around half a perch of bank (approx 2.5 metres) and paid the sum of £1 and 10 shillings annually to the bog agent who resided in Virginia. This man would frequently carry out an inspection on all working banks to ensure that everyone was up to date in their payments. We usually rented a half perch (2.5 metres) but there were many such as the Daltons who cut a full one perch in width bank of turf.

Cutting the turf

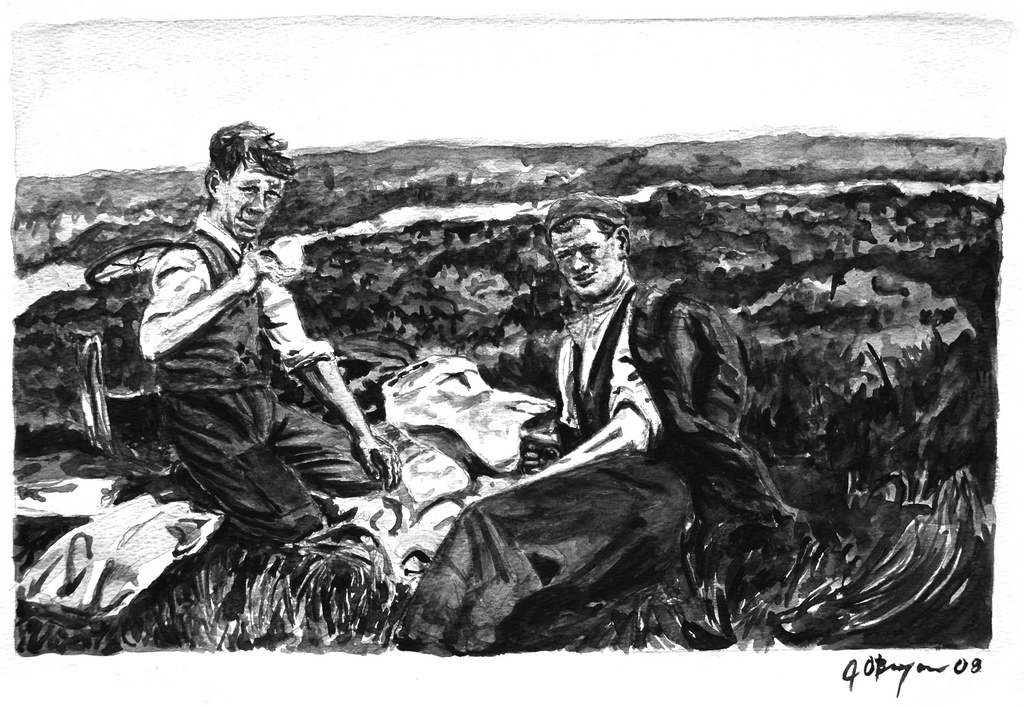

The annual trip to the bog was over a period of two to three weeks, with a workforce of a “slane’s man” and “catcher” or “barrowman” and occurred when the crops were planted and there was time to spare – it was built in to the farming calendar.

The preparation of the turf bank was all important. As this was a raised bog, it had to be stripped of its top layer, generally to a depth of at least two feet – this layer was composed of heather, roots and what we called the light brown turf. It would have been of very poor burning quality. Huge chunks of this were tumbled on to the low bank and into the existing boghole that remained from the previous year. This was firmed up to allow a man and wheelbarrow work with safety and ease when cutting commenced. The top bank was cleaned and squared off until it was as level as a billiard table.

Turf cutters were very exact and took great pride in the preparation of their bank. The implement used in turf cutting was called a side slane – it was generally manufactured to the shape of spade, but was much more refined, smaller and lighter. It had a shortish handle with a tee on the end. But locally, many slane’s men had handles made to their requirements. Its’ sides and forward edges were razor sharp and it was a dangerous working tool. I don’t remember any cutter using a wing slane – this was a similar type slane of more robust proportions with an additional metal wing which was turned up on one side during its manufacture. There was talk locally that some cutters had tried it out.

On the low bank the “catchers” job was to have his wheelbarrow prepared, stand in a suitable position and be able to anticipate and catch the thrown sod from the slanesman, place it on his barrow then catch the next sod and repeat the process over and over again. The barrow man was also skilled at his work – it was his job to make life easy for the cutter by being in the correct position to receive the sod otherwise tempers would rise between the two. Many slanesmen would feed turf to two barrows in order to expedite the work. Each sod had to be placed on the barrow in a particular way, built up until a full load was on board, thus enabling the contents being emptied neatly and tidily – without breaking the sods – in neat rows, perhaps up to 50 yards away.

When work was finished each day, the slane was hid in a particular spot and the barrow was likewise put out of sight, not that anyone would even think of taking the implements!

And so it went, cutting down and down into the bog, with the turf getting darker and darker the deeper you went, until finally one came to uncovering bog timbers and sticks, which signified the end of the turf.

On other occasions, mud turf was discovered at depth and this entailed a different operation to recover the mud which was very valuable and as good as coal.

Going deep brought its own challenges – water trying to seep in to the cutter’s workplace – he was always very vigilant and sometimes it was a continuous battle to keep water out and avoid being flooded. This was where proper preparation of the bank in the first place paid off. People were very careful in their work and in the absence of modern day health and safety, all were very conscious of the dangers in their working environment. I never saw or heard of an accident on the bog despite the very sharp slane and the deep, unprotected bog holes and drains. There were many children helping out on the bog alone, especially when the turf was being “footed”. But we always obeyed the instructions of adults which were drilled into us and therefore we all came home safely. There was no wandering off to explore and maybe get into difficulty or trespass on another bank.

If the weather was good and dry, turf spread out on the after banks dried and hardened and were put into what we termed “squares” – that is four sods laid out with gaps between each and placed one on top of the other to a height of about five or six high. This method hastened the drying and hardening process and after a week or two, the dry turf in these quares were gathered up and put into small clamps which somewhat resembled a rectangular triangle. These were left to dry out further and either eventually made into very large clamps or reeks on the bog or drawn home by horse and cart, put into sheds, or reeks in the haggard. Some families might make two years turf initially, thus ensuring that they only burned turf that was two years old as this would provide better heat and burning quality. The Dalton family from Mullagh were noted for their quality of turf and much of it was three years old.

Eating on the bog

Meals on the bog were eagerly looked forward to – the hard work and the pristine bog air worked up a good appetite. The grub was simple and nourishing – kitchen facilities were basic and military like. A fire was set at an open safe and sheltered location around noon – in a hollow depression – and usually in the same place as in previous years.

We had a sort of shelter which we used for eating – this was on an adjacent disused bank and was beautifully constructed – a sort of an open low cave-like structure, facing out of the prevailing wind. The previous makers hollowed out the shelter from the growing bog and so it remained for years. Food was simple home-made brown bread and butter, chicken sandwiches and eggs which were boiled in the bog water. I recall that spring water for the tea was obtained from a well on John Bracken’s land. A further cup of tea and bread was availed of in the afternoon.

At the end of each day, great care was taken to extinguish the fire completely, by pouring water on it. I never recollected even a small fire occurring during turf cutting season.

Turf cutting families

John Gibney, Mullagh and John Bracken, Leitrim and George Bough, Rantavan were cutting a short distance away from us on Leitrim Bog, as previously mentioned. On the Cloughbally side, Hughie Reilly, Rantavan and his sons Owen and Michael were annual turf-cutters and interesting people to have a conversation with. I remember their father Hughie as a mild-mannered, soft-spoken man.

The Reilly family spent three weeks cutting turf as they had a large bank. They had an ass who was called “Neddy” and a cart equipped with flyers, which they used to draw their turf home. Their sister Bernadette came to the bog from her home twice daily, accompanied by her collie dog “Bruno” – at 1pm and at 4pm – with tea and sandwiches for the men. They never lit a fire on the bog for fear of it getting out of control.

Andy, P.J. and Seamus Mc Kenna from Lislin were cutting on the bank near the Reillys and they also had a large bank to harvest. I remember also the Tully’s from Lislin – their Christian names escape me – they were further over and working away quietly.

Johnny Smith from Cloughbally, also cutting nearby and was always in good form with a joke and a laugh. Stephen Carolan, Rantavan another very reserved man was also on a bank in that general vicinity, as was Kevin Reilly from Lislin – his house was the former home of my great, great grandfather, James Lynch.

Saved turf required to be transported from the soft banks for loading on to large carts on firmer ground. Slipes were often used for this purpose and pulled by an ass. The ass was the ideal animal for working on the bog as its strength and weight facilitated taking loads over very soft ground. In other parts of Ireland, more commonly in Kerry, animals called “Bog Ponies” were used for these tasks.

Vincie Lynch, Rantavan and his brother Mickey were further on and they too had an ass and cart. The Dalton family of Willie and Bernie from Mullagh were excellent turf cutters with particular attention to detail and took great pride in their output and huge reeks of turf. Most days, they brought their horse and cart to the bog to take home some of last year’s turf. Mrs Dalton paid a visit to her sons on the bog at least three times during the season. They always had their fire down and the kettle boiling in anticipation of her visit.

Pat and Tommy Bradley from Rantavan also cut turf. Val Rotchford, Oliver Gilsenan, John Brennan, Matt Feddis, Matt Dalton, Denis and Bobby Nulty, Jack Reilly from Rantavan and his son Tony, all were annual turfcutters further down the line. The Heerys from Lisnagun and the O’Reillys (my uncles) from Ryefield, Munterconnaught and the Muldoons, cut over the Fegat direction.

There were many, many more from near and far whose memory escapes me. The month or so on the bog was a time of social interaction between neighbours from far and near; it was also a welcome break from the manual and tedious work of the farm… it was a great break to get to the bog “for a holiday”.

My father remembers that in his youth, the bog was a hive of activity with hundreds up and down the line busy making provision for the winter months and indeed for all year round, as fires in houses were the only source of cooking – there was no electricity or bottled gas those times.

The bog line was untarred at the time so it wasn’t an easy bicycle ride from Mullagh. Daltons’ was a very well-known and welcoming ceile house in Mullagh where every visitor was assured of a warm roaring fire.

Wildlife on the bog

My recollection is that there was a proliferation of wildlife on Killycunny Bog and the adjacent area. General drainage of farmland was poor and water levels were high. The bog acted as a sponge and released water on a continuous basis, even in dry summers.

The water was unpolluted and pure – older residents would testify that bog trout were in abundance in the larger and deeper streams. I remember seeing on only a couple of occasions, a bog trout in the deep part of the stream adjoining Farrelly’s land at Cloughbally.

Local people remember it being common to catch these trout for their meals and certainly eels were in abundance and a tasty meal.

Farming was still being carried out by horses; oats was grown and either cut by the mowing bar or binder and stooked in the fields. Most people grew an acre or more of other crops such as potatoes, turnips or kale. All of the foregoing factors ensured that wildlife in the vicinity of the bog had therefore a plentiful supply of food and shelter.

The Curlew was a very prolific bird on the bog and in the adjoining bottoms. It was very reassuring to hear their lonely-sounding call which you knew signified that all was well in the adjacent moorland.

The call of the Wilduck was very common and these were equally at home in the myriad of drains around the bog.

Pheasants were not that common as gun clubs were not established – however, wild pheasants could be seen feeding around stooks and stacks of corn in the fields.

Red Grouse were also on the bog but they were few in numbers – my father remembered when their numbers were relatively plentiful nesting in the deep heather and eating a diet of young shoots that grew on the afterbanks.

Red Partridge was also common, as was Snipe whose call, “drumming”, you would hear in the spring time.

Smaller birds such as the Pied Wagtail were common and nested in crevices in the turf banks.

Moorhens or Waterhens were very common and at home in the ideal nesting and foraging conditions provided by drains and relatively still water. Crows, though not associated with bogs, had their rookery in tall scots pine trees on Paddy Farrelly’s land, on the other side of the bog line.

The Cuckoo was also a very common bird and could be heard with great regularity from early spring as it flew among the trees on the edges of the bog. And where you hear the Cuckoo there are Reed Warblers who make their nests – in which the Cuckoo lays her egg – among the reeds.

Sadly with modern drainage, these reeds no longer grow and so the habitat of the reed warbler is lost and, consequently, the Cuckoo. Nature is indeed a very delicate balance.

Woodcock were also prevalent but difficult enough to observe. There was the odd Kingfisher at home on the faster flowing bog drains that came off farmland. These invariably had what we called minnows or “pinkeens” for their daily diet and these small fish seemed to be in abundance in particular areas of the streams. Holes in the soft peat banks provided readymade nesting sites for kingfishers. Dragonflies of all sizes were another visible, very common and colourful insect as they hovered over bogholes and turf banks. There were some quite large ones and were always a mystery to us, as to how they survived. Somehow, for whatever reason, they don’t seem to be as numerous nowadays, and certainly not as big as they once were.

Midges for such a small insect were an infernal annoyance and would literally eat you alive in the late evenings. Bernadette O’ Reilly always wondered at the number of bats she noticed flying at dusk, as she went home on the loaded ass and cart with her father via the bog line – the preponderance of midges was the answer. She was also blessed by the sight of many Barn Owls, flying silently around dusk and earlier, again while on the bog road. Perhaps the owls were hunting the bats for food which were hunting the midges!

The holes in numerous mature trees in the area and a short flight away in Mortimers, facilitated their nesting and also at that time, several old corrugated and disused stone sheds were ideal habitats.

Frogs were numerous and the readymade still pools of water proved to be excellent breeding habitats. Mammals such as Hares were quite common, and were visible running across the fields on the edge of the bog. It is therefore true to say that the bog and its general environment at the time was protection and home to quite a variety of wildlife.

Glow on the bog

My father remembered seeing at certain times of the year an unusual phenomenon of a glow or faint light coming off the wet bottoms at night time; these adjoined the bog and he could never say what caused this luminescence at low temperature! Perhaps the habitat has changed and whatever was glowing has become extinct…

Essential tools of the trade

The Slane. (Slean as Gaeilge) These were manufactured for the most part locally and generally by a blacksmith. This item was a prized and valuable possession. The blacksmith made almost everything that was needed in the farming line. He was an important man and his status and pecking order in society was somewhere between the Parish Priest, the Schoolteacher and the Miller. With his anvil, bellows and a stout sledge, all accompanied by muscle power and driven by an inventive brain, it was indeed possible for him to make literally anything. He also made spades and shovels, first cousins of the slane!

Blacksmiths such as P. Clarke who had a forge at the time in the townland of Killeter on the Mullagh to Bailieborough road made slanes amongst many other things. Other slane makers in the general locality would have been Mr Mc Entee (aka “The Toy”) who operated a forge at Cross, Mullagh and Tommy Flanagan’s forge at Ryefield, Mounterconnaught, Virginia – this was a very advanced forge and also made ploughs, etc. Terry Boylan was a busy blacksmith at Virginia Road Station and his son Mick carried on the business after him (a high class restaurant now operates from this former forge). All of these and other numerous blacksmiths were capable of turning out a slane if required.

The bog barrow was generally constructed by the local carpenter and was of easier construction than the normal working barrow with sides. Makers of these were carpenters such as John King, Bailieboro who also made carts, gates, slipes and feeding troughs and sold them at Mullagh Fair; the Gaynor brothers of John, Owen and Paddy of Cornaglea, Mullagh made barrows, slipes and horse carts; James Farrelly, Cornakill, Mullagh also made barrows and slipes. Kelletts in Virginia also sold barrows.

The slipe was a common farm vehicle designed for conveying small loads from awkward places and pulled by a horse, pony or ass. It was of stout timber construction on two raised wooden runners that were shod with a light steel plate to facilitate its smooth travel over ground and protect the runners from wear. This was an excellent means of transporting turf off the bog to another suitable location. In short, it was a sort of Irish sleigh or sled and every farmer had one for performing numerous farm asks and was especially suitable for the youth. They were made to various sizes but generally were no more than four foot in width and perhaps six feet in length.

It is safe to say that all of the above essential items for bog work and turf cutting were manufactured in the general locality by artisan craftsmen and would have been used season after season.

Curative properties associated with the bog

It was commonly agreed – rightly or wrongly – that bog air was possessed of particular goodness; that time spent on the bog breathing this refreshing air could only make one feel much more relaxed. There may be quite a lot of merit in this long held belief as air flowing over a bog is cleansed and infused naturally with micro particles of the flora growing in the area and the odours emitted from the breakdown of peat.

Bogs are generally devoid of adjacent large urban housing estates, traffic and factories and therefore are naturally occurring pollution free environments. All good for one’s health!

Persons working on the bog were encouraged to go barefoot, except for the turf cutter who risked injury to his exposed feet with the slane. After only a few days on the bog, one would notice that their feet took on a yellowish brownish pigmented colour. This came about as a result of the tannin and other properties coming in contact with the skin and as far as I know, was quite harmless and may have been beneficial for some skin ailments. When making mud turf on the bog, it was customary to tramp the mud (break it down to an even consistency) in your bare feet. After a hard days barefoot work on the bog, your feet would feel very refreshed – no need for deodorants or powders.

My grandfather had an unusual method of helping to heal an open wound or cut to the skin which was handed down through the generations. It involved going to the bog and taking some of the mesh like fauna (more commonly known as Sphagnum Moss) growing on top of the boghole water and placing it over the cut, thus sealing it, covering it with a bandage and speeding up the healing process.

Modern science has since discovered and proved that this Moss is indeed sterile and ideal for dressing wounds. Much the same as propolis from a bee hive acting as a barrier against disease in the hive and a mild cure for a sore throat. These locally known, home-based first aid treatments came about as a result of long term observations by our ancestors and though primitive, probably saved many lives in the past.

Other uses of turf.

It was common for the roof of a primitive animal shelter or shed to be made of turf. The turf surface on the after banks in these instances was scraped clean of heather, lifted and roughly rolled up in sections about eighteen inches wide with a depth of about six inches. It was then placed tightly as the outer layer over a lattice roof of sally rods covered with rushes. The walls were of rough stone and the rear wall of the structure would probably have been a boundary ditch of a field thus keeping building to a minimum with ease of construction. This would have been a warm enough shelter for animals and in the not too distant past, we Irish had to live in such structures during and after the famine and in many instances, these dwellings were located on bogs and in deep gripes that were likewise covered with sods of rolled turf.

Building a Kesh (Gaelic: Ceis)

To gain access to the bog from the roadway or adjacent land required in many instances, the construction of a small bridge over large drains and this structure was commonly referred to as a “Kesh”.

This was basically a wicker type structure made of trees, small branches, rushes, sods, etc. and the word itself is Gaelic for a wicker basket. Interestingly, turf was sold in the past in “kiskes” or “keshes” – large wicker basket measures.

Keshes or small wicker type bridges were very common all over Ireland. The kesh was of sound though primitive build and well capable of taking the weight of a horse and cart fully loaded with turf. They could in theory be built to any specification. My father had to rebuild a “kesh” on several occasions and from the memory of helping him with the task, the process was as follows:

– After selecting the narrowest and most robust area on either side of the drain and sound bank on the bog side, several “sally” trees were cut and stout strong lengths were placed across the drain, imbedded into the banks. The width would have been sufficient to take a horse and cart with safety and it was important to place several lengths of this timber in the centre to support the weight of the horse and it’s pull on the load. Likewise, particular attention had to be paid to the area carrying the narrow cart wheels.

– Following on, smaller lengths of fresh cut timber were laid at right angles in rows on the main supports. This then was covered in rushes and a thick layer of bog sods was laid on top to complete the job.

– There were some variants to this construction but basically all cesi builds were similar. After a short time growth would appear on the structure and make it that bit stronger. In many instances, it was impossible and too dangerous to attempt such an enterprise and turf had to be taken to the roadside by a slipe. Indeed, some reeks of turf were built initially at the side of the road rather than on the bank to save valuable time and labour.

Conclusion

The Great Bog Of Mullagh or Killycunny Bog as it known to my family, was of great importance to the native Irish down the centuries. Populations prior to English rule were numerous millions more than today with most living in rural areas. The Brehon Laws were composed of a huge body of intricate legal tract over a long period of time and to support these laws, required a substantial population.

We will never know but we can surmise that Killycunny Bog or the Bog at Mullagh provided a ready-made source of heat, shelter for the homeless, some curative qualities and food over the millennia for this large population.

Bogs are still very dangerous places because of the abundance of deep watery bog holes from times past and camouflaged drains with overgrown heather waiting to take the unprepared. To make it possible for generations to enjoy with safety Killycunny Bog, it would therefore be very remiss of us in these enlightened times, not to take the necessary measures to protect and enhance that existing resource created over the millennia, and in memory of our native relations who came from near and far and took so little of it while experiencing dire poverty.

Note from the author: Background

I am conscious that there are many others more knowledgeable and far better experienced than me to comment on this subject and The Living Bog would therefore be delighted to hear from you.

For what they are, my thoughts and recollections above are not meant to be a definitive statement that all would have experienced, but rather my own account and as we all see and observe things in different shades of light, you the reader, are asked for your story, to add to this general body of knowledge before it is lost. Get in touch with Ronan from the LIFE Project or any committee member at St Killian’s Heritage Centre if you experience difficulty putting pen to paper and you will gladly be helped.

If it is to be revived locally, the annual “Bog Day” festival – being out in the “Bog Air” – should hopefully revive our memories and give us all a better experience and understanding of the hard work of our ancestors in the not too distant past”

Disclaimer:

*Please note, this is a personal account of life on the bog, and is published by kind permission of the owner and author of this work, John K Lynch. It is in no way intended to cause offence to living or dead and the LIFE team disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. If amendments or edits need to be made, please contact us and we will pass them on.

The information provided here is designed to provide a background on the bog. It is not meant to be used for any other purposes, and our publication of it does not constitute endorsement.